Medetomidine (pronounced med-deh-TOH-mih-deen)

Medetomidine, sometimes called Rhino Tranq, Tranq-dope (combination of medetomidine with fentanyl or other high potency opioids), or Dexmedetomidine (medetomidine’s dextrorotatory enantiomer, but we’ll get to that later), has become drug of concern over the past couple years.

Presence In Toronto Drug Supply

Since Medetomidine was first detected by the Toronto Drug Checking Service on December 29, 2023 (1), its presence in Toronto’s fentanyl supply has grown rapidly. By January 23, 2024, it was already in 11% of expected fentanyl samples, all of which were combined with at least one high potency opioid (1).

Between February 2024 and July 2024, Medetomidine prevalence in Toronto doubled to 24% of expected fentanyl samples. Between August 2024 and January 2025, Medetomidine rose again to 33%. Between Feb 2025 and July 2025, Medetomidine was found in 37% of samples (worth noting that during this time Xylazine was at its peak, being found in nearly 46% of all fentanyl samples). And between August 2025 and December 2025, Medetomidine presence spiked to 79% of all expected fentanyl samples! (2)

Health Effects

Medetomidine exhibits biphasic effects on blood pressure. It can briefly though sometimes dramatically increase risk of hypertension (high blood pressure) upon taking large doses, though shortly after blood pressure drops, and users are at a greater risk of hypotension (low blood pressure) (3). Medetomidine can also cause nausea, bradycardia (heartbeat slower than 60/bpm), and hypoxia (lack of oxygen). All of these health risks dramatically increase when combined with other sedatives such as opioids or benzodiazepines.

Medetomidine withdrawal may result in extremely high blood pressure, tachycardia (heart rate faster than 100/bpm), nausea/vomiting, anxiety/agitation, and tremors (4). Medetomidine withdrawal can pose many health concerns, and people going through withdrawal sometimes require intensive hospital care and various medications to manage withdrawal symptoms (4).

Chemistry/Pharmacology

Medetomidine is a racemic mixture of its two enantiomers: Levomedetomidine and Dexmedetomidine. Levomedetomidine is believed to be largely inactive, though it may function as an a2-AR antagonist when taken in extremely high doses (several hundred times dexmedetomidine’s active dose) (5). Dexmedetomidine is responsible for medatomidine’s effects, and as a result is twice as potent by weight compared to medetomidine in its racemic form (6).

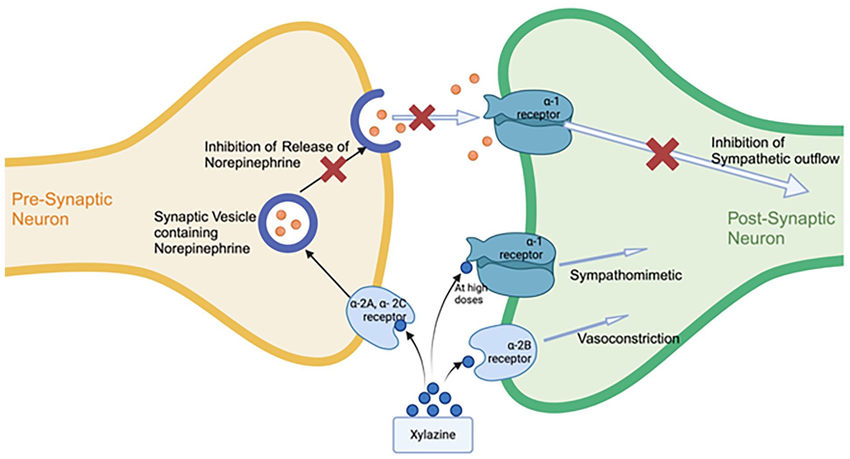

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective alpha-2 adrenergic receptor (a2-AR) agonist. It causes sedation and analgesia (reduced experience of pain) by binding to a2-AR (specifically the a2A adrenoreceptor subtype, which is most responsible for the presynaptic inhibition of norepinephrine release) (7). This becomes particularly relevant when comparing it to the other most common a2-adrenoceptor agonist combined with opioids, xylazine. Xylazine is less selective, and its activity at the a2B-adrenoreceptor (which induces vasoconstriction), is partially responsible for the skin lesions and soft tissue damage associated with its usage (8). Medetomidine does not seem to induce similar tissue damage (4). It is worth noting that while it is often found in slightly lower doses in fentanyl samples than xylazine is, the reduction in quantity is nowhere near enough to offset the dramatic difference in potency (medetomidine being somewhere between 100-200 times more potent). It can greatly amplify the respiratory depression induced by other sedatives when used together. While it is most often found mixed in with opioids, it is not an opioid itself, and does not respond to naloxone administration (though given how commonly it is found with opioids, if a medetomidine overdose is suspected naloxone should still be administered!)

History/Medical Usage

The earliest mention of medetomidine is found in a patent filed in 1981 (and published in 1983) by Finnish pharmaceutical company Farmos Group Ltd (10). The earliest optical resolution of medetomidine (preparation of dexmedetomidine) is mentioned in a patent filed by the same company in 1987 (published in 1990) (11). Dexmedetomidine received FDA approval in 1999 as a short term (defined as less than 24 hours) sedative and analgesic for people on mechanical ventilation in intensive care under the brand name Precedex (12).

It is sometimes preferred to other sedatives as it may blunt the effects of emergence delirium and is often used as an adjunct in general anesthesia (13). Dexmedetomidine also received FDA approval to treat “agitation” associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia under the brand name Igalmi in 2022 (14), and is used off label to manage withdrawal symptoms from a variety of downers, most notably opioids (15). Atipamezole was developed as a reversal agent for medetomidine, though is not approved for human usage (16). Medetomidine is largely used in veterinary contexts as a sedative and analgesic. It is also sold in freebase form as an antifouling substance for marine paints (17).

Dexmedetomidine was approved in the EU for cat and dog usage in 2002 as a sedative and in general anesthesia induction under the brand name Dexdomitor (18). FDA approved Dexdomitor for use in dogs in 2006 (19) and cats in 2007 (20).

The first record of non-medical human usage of medetomidine was 12 samples, 2 from Virginia and 10 from Ohio, documented by the National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) in 2021 (21).

Overall, medetomidine/dexmedetomidine continues to become more prominent in Toronto’s drug supply, particularly drugs sold as fentanyl. It notably increases the risk of overdose when combined with other sedatives and complicates overdose recovery/treatment as its primary effects are not reversed through naloxone administration (THOUGH NALOXONE SHOULD ALWAYS BE ADMINISTERED IN CASES OF SUSPECTED MEDETOMIDINE OVERDOSE).

Stay safe everyone 🙂

Citations:

1. Medetomidine – Toronto Drug Checking

2. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/karen.mcdonald5803/viz/Newproposedwebsitevizs/DB-Otherdrugfound

3. https://journals.lww.com/anesthesiology/fulltext/2000/08000/the_effects_of_increasing_plasma_concentrations_of.11.aspx

4. https://hip.phila.gov/document/5444/PDPH-HAN-SUPHR-Medetomidine-06.10.2025_1Zu1OZ4.pdf/#:~:text=Medetomidine%20can%20produce%20a%20severe,and%20intractable%20nausea%20and%20vomiting.

5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1682487/#:~:text=The%20biological%20activity%20of%20MED,relationships%20at%20alpha%2D2%20adrenoceptors.

6. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7401557/#:~:text=Simple%20Summary,rapidly%20when%20atipamezole%20was%20administered.

7. PMC1291306

8. NBK594271

9. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Mechanism-of-action-of-xylazine-Xylazine-acts-primarily-as-an-alpha-2-adrenergic_fig2_392840381

10. EP0072615A1

11. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/US-4910214-A

12. 21-038_Precedex.cfm

13. PMC4389556

14. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2022.05.5.10#:~:text=Encouraging%20News%20for%20People%20Experiencing,Igalmi%20is%20manufactured%20by%20BioXcel.

15. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3276827/#:~:text=Dexmedetomidine%20infusion%20was%20successfully%20used,from%20opioid%20and%20other%20sedatives.

16. ANTISEDAN

17. https://www.pcimag.com/ext/resources/WhitePapers/2016/The-Selektope-Story-v2.pdf

18. https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2002/200208305572/dec_5572_en.pdf

19. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2007/01/04/E6-22508/implantation-or-injectable-dosage-form-new-animal-drugs-dexmedetomidine#

20. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2007/09/07/E7-17696/implantation-or-injectable-dosage-form-new-animal-drugs-dexmedetomidine#

21. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11537807/